In order to do your job, you need to see your job.

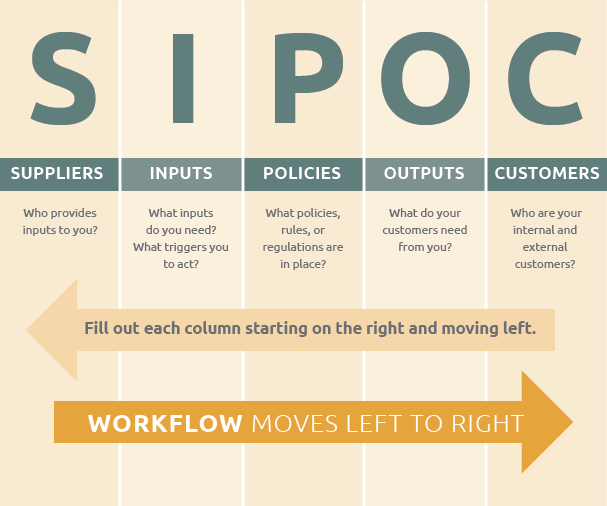

As some of you already know, SIPOC is a process improvement tool that helps you do that. For those of you who are less familiar with the term, “SIPOC” stands for Suppliers, Inputs, Policies (I’ll discuss this in a moment), Outputs, and Customers. The acronym sounds a bit scary, but it’s really just a table that shows your work in a visual format—five columns of information, as shown above.

The first step in lean is to identify value from the customer’s perspective. So, when you’re building a SIPOC table, you’ll actually start on the right-hand side of the page by filling out a list of your customers. Looks easy at first, but wait a minute—who exactly is your customer, anyway?

Define Your Customer

In the business office, a customer is anyone whom you give things to directly, internally or externally. On the road to satisfying the end user or traditional customer, there’s a long line of internal handoffs that must be completed first, and in sequence. If those internal handoffs aren’t successful, then the end user will never be satisfied without a lot of rework and waiting.

For example, I provide a checklist of materials to our internal coordinators at the University of Tennessee, who in turn ship books and orange pens to off-site class locations. So those coordinators are my internal customers. The finance department at UT is also an internal customer—after all, they receive my expense statements, right? If I don’t do them correctly and on time, then there’s no expense reimbursement. Anyone who receives something from me is an internal customer, no matter how small the “something.”

Some business process results never reach the end user or external customer at all, so the internal customer is the only one. Here’s food for thought: when you hit “send” on an office email, whom does it go to? Those are your customers.

Be Clear About Your Outputs

Once you have your full list of internal and external customers in mind, make a list of all the outputs you provide. I provide my external customers solutions in the form of training classes, facilitation, and consulting. I provide a T3 expense statement to finance, and the checklist previously mentioned to coordinators. It’s important to be specific about items you provide and not just use ambiguous words like “support” or “oversight” unless there’s really no other way to describe it.

Try to define your outputs as best as you can. Think of each one as an item on a restaurant menu: you need to know every dish on the menu so that you can start to create a standard and best practice recipe for each.

And Now, a Twist: Focus on Policies

Now we’ve come to the middle column of our SIPOC table, the “P.” Traditionally, in lean, the “P” stands for processes.

And here’s where Lean Applied to Business Processes adds a twist. When you’re filling out a SIPOC table for the business office, the “P” stands for “policies” instead, for two reasons. One: in business processes, the biggest constraint we face is our policies, either real or imagined. It’s critical to address them up front. The second reason is that my LABP methodology covers process in the next step after SIPOC, where I help you create a high-level process map that’s much more visual (and more effective) than a list of words.

I bet you can make at least one large reduction in lead time or touch time by identifying a misinterpreted or outdated policy.

So for now, let’s focus on policies rather than processes. In the Policies column, list all the rules, regulations, and even urban myths that govern how you must provide the outputs to each of your customers. All of you working in business processes are professionals who should be experts in the policies that guide how you do your jobs. In my experience, I find the most common errors (rework and wasted time) come from either 1) not following the rules or 2) following rules that don’t exist—urban myths.

Think about it: how did you figure out the rules for your job? Typically, when you start a position, someone tells you what you can and cannot do. And that person likely learned the very same way, from the person who came before.

How accurate do you suppose that method is? Here’s a clue: every Value Stream Mapping event I’ve ever been a part of has had at least one large reduction in touch time and lead time through the discovery and correction of a misjudged policy.

What Input Do You Need, and from Whom?

Next, provide a list of the inputs you need to make your output. Starting, perhaps, with a trigger. What typically causes you to act? A request? Timing? What information or approvals do you need?

Finally, to the left of inputs, make a list of all the suppliers who provide you with those inputs.

A Visual Map for Process Improvement

Now, take a look at the map you’ve created of your job. Is it complete? Was it hard to come up with? Was this the first time you’ve ever given some of these connections any thought? You may still have some holes to fill, and that’s to be expected. That’s part of the work of LABP.

But there are things you can do with the information you’ve collected now. The table you’ve created is a great tool for scoping and communicating a process improvement initiative. And you can start within your circle of influence. Here are the action steps you can take:

- Go talk to all your customers: Are your outputs 100% complete and accurate? (My bet says no! Go ask!) Are you providing anything to your customers that they don’t want or use? Again, my bet from experience is that you’re wasting time by adding information for your customers that they don’t need.

- For every output, produce a checklist or template of the best practice of how to produce that output. Any variation between how you do it one time vs. another, or any variation between how you do it vs. how a co-worker does it, will cause delay, excess inspection, and rework, even if it isn’t wrong.

- Read, understand, and socialize your rules and regulations. They are usually high-level, which means there are probably as many interpretations of them as there are people who execute them. Talk about this with your colleagues.

- After steps 1 through 3, prepare a checklist of all the inputs you need to complete your outputs.

- Ask your suppliers to follow the checklist of how and when you should receive your inputs to prevent delay and rework. How many of you had the epiphany that your supplier is also your customer? The one providing the trigger also generally receives the output. Tip: if you’ve already achieved steps 1 through 3 before you ask anything of your supplier, you’ll improve your relationship and increase your influence.

SIPOC may look like another difficult acronym of random letters pulled from the alphabet, but it is actually a very helpful schematic. It’s an exercise that helps you see your job better, increasing your sense of urgency, situational awareness, and synergy—your ability to share your menu with your customers and co-workers.

Many of my clients want to skip the SIPOC step before they get to doing the meaty work of process improvement because they don’t see the benefit. But that’s like getting a mechanic to replace parts of your car to improve its performance based on guesswork, instead of isolating the car’s problem in an organized and efficient way.

You hold an important role in your organization’s processes, and you should have a professional way to troubleshoot that role so you can decrease the time and cost to provide what you do. SIPOC—with the twist of “P” for Policies—is just what’s needed to get you on your way.