Teaching Lean Applied to Business Processes is never dull. But once the conversation turns to finding value in the steps of a business process, things get downright crazy in my classroom. Students argue with each other. They argue with me. Once, someone was so upset by the discussion that he stormed out.

Why all the fuss? We’ll get to that. First, let’s talk about value.

The Customer’s Perspective

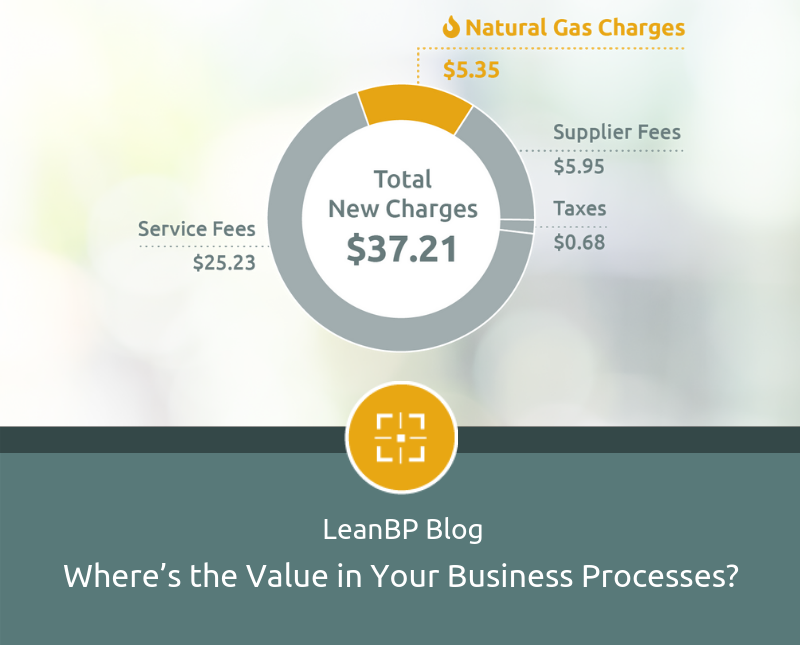

Natural gas service is a wonderful convenience that I don’t take for granted. Still, looking at the bill gives me pause (see the illustration above). Note that my actual gas usage is nearly the smallest charge at $5.35. (This bill was from the late spring, when my daughters weren’t home draining the tankless water heater.) This transparency—what we call “seeing the process”—allowed me to recognize that most of my gas charges are non-value added (overhead). They’re required in order for me to receive service, but they don’t make my water any warmer.

When applying lean, the first step is to identify value from the customer’s perspective. What outcome is the customer seeking? Certainly, many retail and service organizations spend untold time and resources trying to figure what value their customers are willing to accept for their hard-earned money. Then the organization tries to focus the front line to assemble or deliver those value-added products and services.

It’s the same for business processes, where the first step is still to identify value from the customer’s perspective. In most organizations, there’s usually a large staff who are doing nothing but processing information (read: overhead). Currently, competitive markets don’t want to pay for overhead. Much of this work is not actually valued by customers; it’s done to support the front line or for internal purposes. When those internal purposes include tracking and reporting, prioritizing and reprioritizing, expediting and facilitating, batching, multitasking, rework, and finally compromising quality and content to meet deadlines, you’re truly getting into stuff the customer wants no part of.

A glance at your utility bill gives you some idea how many non-value-added tasks get passed along to the customer as overhead.

Still other activities may be required by regulation or even the boss’s whim. Some are due to the variation between workers and how each prefers to do his or her work. And in government and higher education, the list of non-value-added activities often becomes alarming. The point is that if customers had a choice, they wouldn’t want to pay for those activities—so they’re non-value added. Unfortunately, customers are paying for them. They’re embedded in the price, as in the gas bill above.

Historically, lean has been applied mostly to front-line workers in assembly, repair, and services, which is understandable. They’re the people providing the most value. But this overlooks a critical problem: an organization’s overhead processes are frequently a constraint to the front line’s business.

Who is the customer in overhead processes? It’s usually the front-line person, another overhead person in a long line of hand-offs, your boss, or an external regulator like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Because lean has yet to fully address overhead processes, those processes have become a constraint that the front-line employees must wait on, and a bloated cost to doing business that makes the front-line employee non-competitive. Ideally, every single process should be vetted for elimination or improvement. But if the current climate doesn’t allow that, then you should aim to reduce lead time and cost to improve delivery to your customers. How?

The One Question You Must Ask

If you’re an administrative employee who doesn’t touch the external customer, your customer is the person you hand off your product or service to—the person who receives when you hit “send.” (SIPOC is a useful tool for determining who your customers are, by the way.) Figure out what the next person in the process needs to be successful—in other words, figure out what your customer values. The best way is to ask each one directly. Here’s the question you should ask:

“Am I providing everything to you that you need, 100 percent complete and accurate, and is there anything I’m providing that you don’t need?”

Trust me—very few people ever ask this question. It’s an amazing opportunity to reduce rework and just stop doing things no one needs. Most recently, I’ve worked with a client who delivers financial analysis to program managers in an aerospace and defense process. When the client posed the above question to a program manager, the PowerPoint analysis deck his team provided shrank from 250 slides per month to 130 slides, allowing for less time on reporting and more time on analysis. This effectively swapped a less valuable task for one with more value.

“Never pass defective items to the next process.” —Taiichi Ohno, Former Executive Vice President of Toyota Motor Corporation

What’s the Controversy?

The act of determining value to your customer seems as though it would be straightforward. And always positive. But the truth is that it can be unsettling for people who do it. I told you my classes get tied up in knots over whether a step in the process adds value. That’s for two reasons: one, thinking in terms of customer value requires a sharp paradigm shift that isn’t easy to process, and two, it can be unnerving to discover that most of what you do adds no value to the end customer.

Let’s talk about the paradigm shift first.

Step two of lean is to break down and visualize the all the steps of a process in order to create value, including the wastes and non-value-added steps. This task is called value stream mapping. It’s best to scope a process by finding and focusing on its biggest constraint or bottleneck rather than mapping the entire enterprise, which is a bigger bite than anyone can chew. You don’t want to create too much WIP (work in process), even in the spirit of improvement.

- Map out each step at a detailed level (using sticky notes)—that’s where the wastes are.

- Using a red dot, identify steps that would not be considered value-added from the perspective of the person or department you hand off to. Start with what appears to be the most egregious. Consider . . .

- Which steps are done only for your department’s or your internal purposes

- Which steps really do not change fit, form, or function

- Which steps your customer would not want to wait for; essentially, internal customers “pay” in lead time for you to do tasks that are not value-added

- Place a green dot on the steps deemed to be value-added. There will be far fewer green dots than red—usually fewer than one-to-ten if you used enough detail in the mapping.

- Use a cause-and-effect diagram to identify wastes.

The difficulty lies in the fact that a step may be non-value-added, but currently required nonetheless. This usually throws students for a loop. To see the opportunities, you must think as if your customer had a line-item veto. All steps have costs. If your customer had a choice, which steps would he or she cut rather than pay for?

That’s not to say we should immediately cut those steps, because that can set the system up for failure. Instead, you can use the 5 Whys to determine the root cause of the non-value-added task or waste. Then focus on improving those non-value-added steps and wastes rather than trying to increase the speed or reduce the costs of the steps that actually add value.

Another tricky point in this exercise is that it’s subjective. Unless you can ask the customer directly, it’s hard to say sometimes what adds value and what doesn’t. Plus, in some instances, the customer doesn’t always know what’s best, like the patient who just wants the doctor to provide the prescription and not run the tests. In the case of the financial analysis above, the slides deleted were of no value. Some of the remaining slides were considered non-value-added only because the program manager didn’t understand the benefit of some of the analysis. After this was clarified, the non-value-added content was removed and the value-added content emphasized.

Focus on Tasks, Not People

Finally, I’ll address the touchy part of this topic. “Value-added” and “non-value-added” are labels intended for process steps, not the people who carry them out. And remember that we’re talking about the customer’s perspective, not the organization’s. Your goal when you find wastes is not to eliminate the people doing the wasteful tasks—it’s to eliminate the wastes, allowing those employees more time to add value and support the functions they were designed to support. You can then take any excess capacity and put it toward growth rather than running in place.

I once worked with a client who was a senior buyer for aircraft component repair. Hundreds of parts were back-ordered, increasing the lead time for repairs and triggering penalty discounts on customer invoices to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars. The buyer was purchasing parts reactively at higher costs, and often with expedited shipping. She spent a lot of her day just tracking the status of orders and providing reports. The value stream map showed that what she did was mostly non-value-added—her team thought her job should probably be eliminated, and she was inclined to agree (she hated what she was doing).

But this was her actual job description: to provide parts on time to the first line technician while balancing low inventory. That’s a valuable job, not one that should be eliminated. So the team worked to eliminate her non-value-added tasks so she could spend more time on balance forecasting and reducing inventory. And it worked. Overall, the company’s efforts to apply lean business processes improved metrics almost everywhere, including reducing inventory by 39 percent and growing its profit margins by five percent. It created excess capacity in facilities and staff that could be used for expansion without additional capital outlay.

Determining the value in your business processes isn’t about eliminating jobs. It’s really just critical thinking about costs and delays that result in overhead and lack of competitiveness. Lean basically amounts to tough love. Sometimes the analysis comes as a bit of a shock to the workers involved, but the most important thing is that it pushes you to a different kind of thinking.

There’s also a valuable side effect of going through the exercise of value stream mapping. When you’re able to identify and articulate the value you provide to your customer, you’re actually articulating the value you provide to the organization. I can’t think of a better way to approach your yearly personnel evaluation than by presenting that information, plus a plan for optimizing that value for internal and external customers over the coming year.

What better reason to start mapping your processes and thinking critically about improvement? On that positive note, I wish you a very happy holiday!

Very good blog. Good information to apply to current business practices.

Comments are closed.